In March 2023, the European Parliament voted for a more aggressive phase-down of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) gases, aiming for a full phase-out by 2050 and banning HFCs and HFOs in multiple applications from January 2026 and 2027. However, negotiations aren’t expected to include until summer and on 5th April 2023, the European Council brought a more lenient approach, relaxing the quota step-down.

Please view our new updated article to find out more https://www.star-ref.co.uk/smart-thinking/the-new-fluorinated-gas-f-gas-regulation-phase-down-draft-proposal-april-2022/

Hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) gases, typically referred to as F-gases, are manmade chemicals developed for use as refrigerants in the HVACR industry. They have been widely used as replacement fluids for ozone depleting gases such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) as part of the phased-out programme under the Montreal protocol.

F-Gas Regulation

Although HFCs have no detrimental effect on the ozone layer they contribute towards global warming if released into the atmosphere. Legislation has been introduced at a national and international level in order to combat the effect of F-gases on climate change.

The European F-gas Regulation EC 842/2006 was implemented in 2006 and updated in 2014 (EC 517/2014). It was a landmark ruling that provides a clear path for manufacturers, installers, specifiers and operators of refrigeration, air conditioning and heating equipment to phase down the use of the most environmentally damaging refrigerants and introduce lower global warming potential (GWP) alternatives.

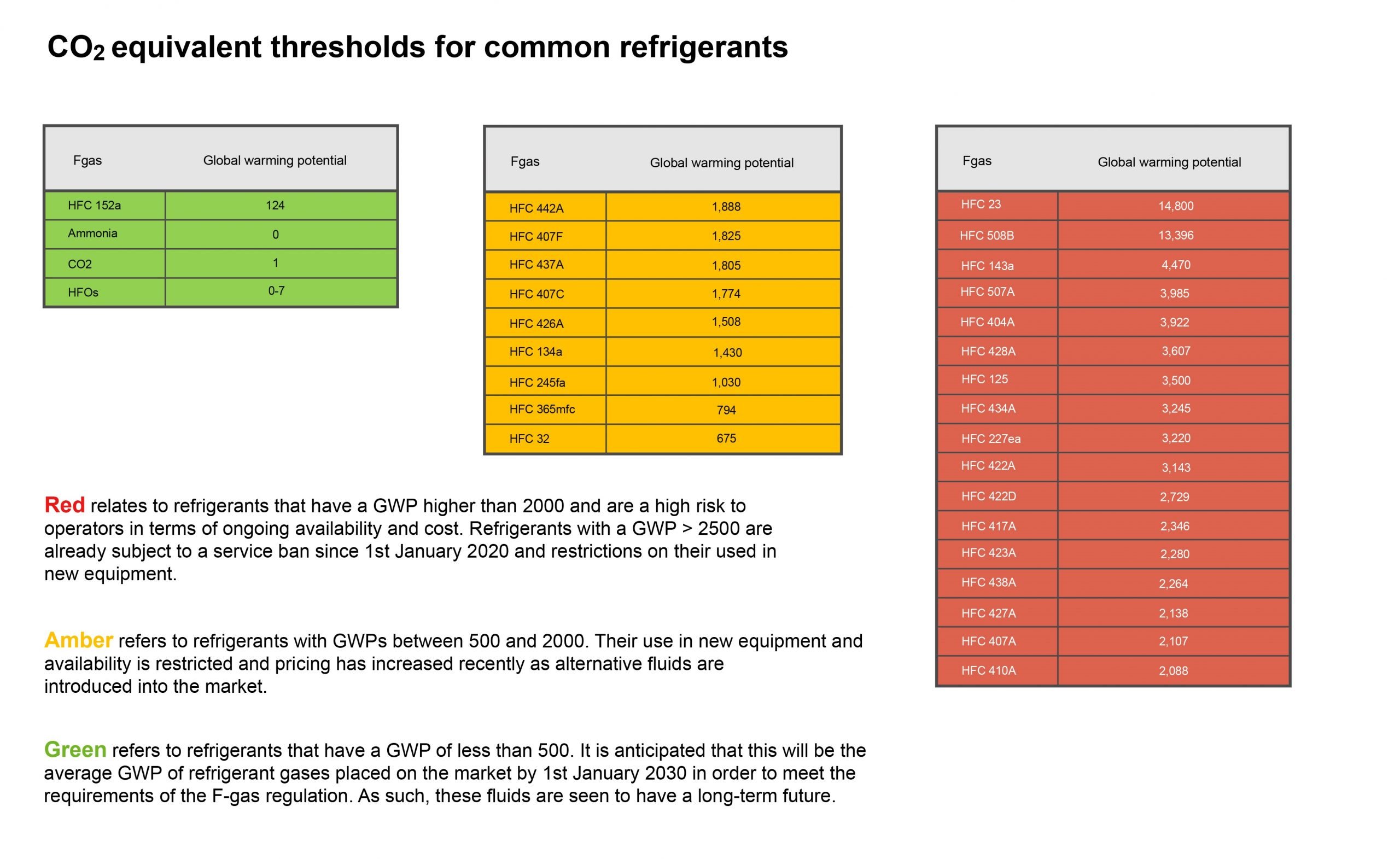

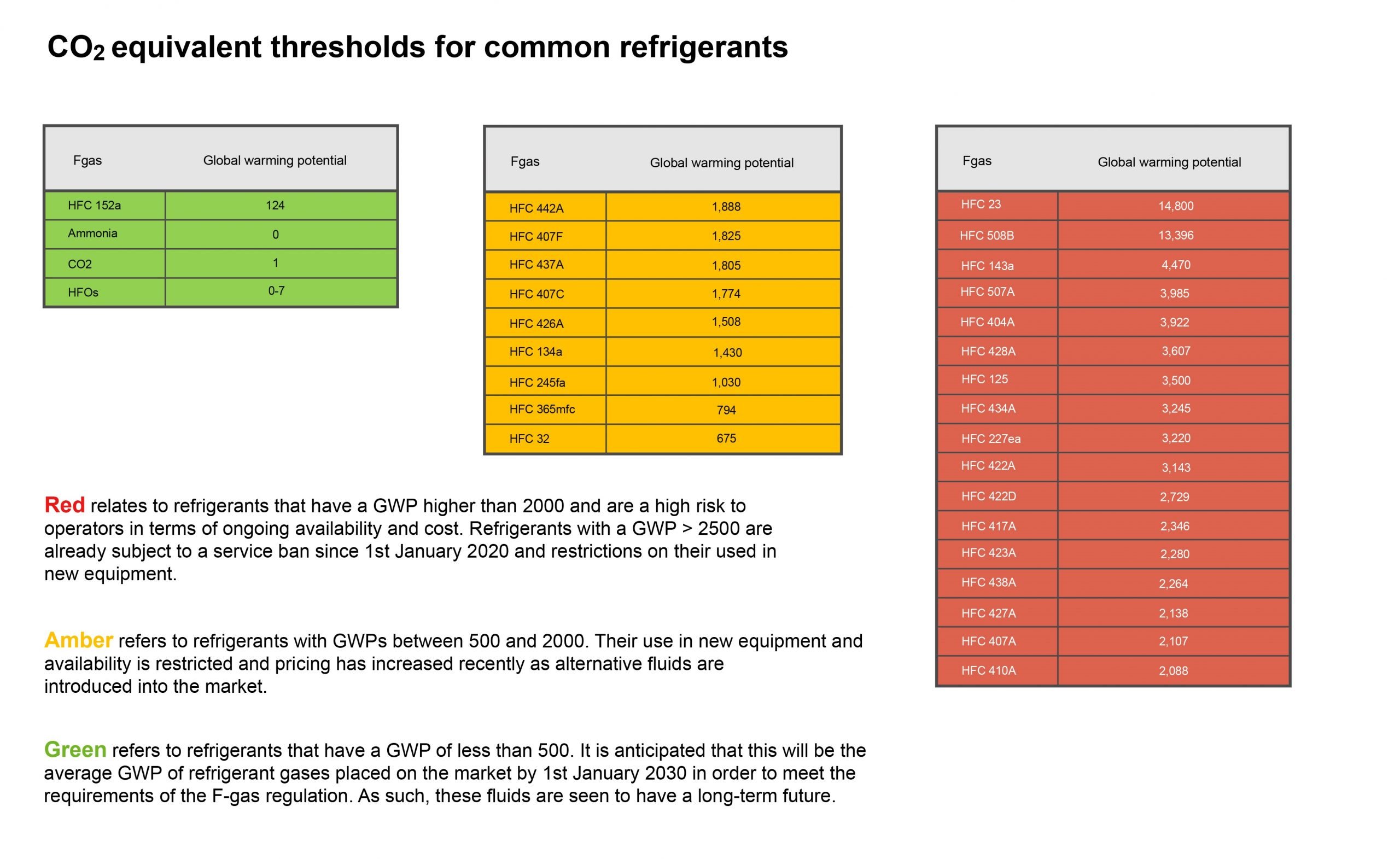

The regulation refers to carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent as a measure of how much a gas contributes to global warming. This uses CO2 with GWP of 1 as the baseline fluid for comparison. To calculate the CO2 equivalent of a quantity of a refrigerant, the mass of gas is multiplied its global warming potential (GWP). For example, R404A (the widely used HFC refrigerant) has a GWP of 3922. This means that 1kg of R404A contributes the equivalent of 3922 kg of CO2 if released into the atmosphere. A table of commonly used refrigerants and their associate GWPs can be found in figure A.

Fig.A Table of commonly used refrigerants and their associate GWPs

To mitigate the potential environmental impact of F-gases, limitations around their use were introduced in the 2006 F-gas Regulation. An update in 2014 added further measures to phase down fluorinated gases with high GWPs in order to achieve a total reduction in equivalent CO2 of 79% by 1st January 2030. This regulation included a ban on the use of newly manufactured HFCs with a GWP greater than 2500 from 1st January 2020 for servicing refrigeration equipment with a CO2 equivalent charge greater than 40 tonnes. This may appear to be a large figure but in the case of R404A, it relates to a system charge of just over 10kg. In practice terms it means that when there is a leak of refrigerant with a GWP higher than 2500 from a system, it will need to be replaced by reclaimed/recycled refrigerant of the same type or an alternative fluid. Whilst the purchase and use of reclaimed refrigerant is a viable short-term option, it should be noted that these stocks are finite. Therefore, this should only be viewed as a temporary solution until a more permanent solution can be implemented.

Drop-in Refrigerant Replacements

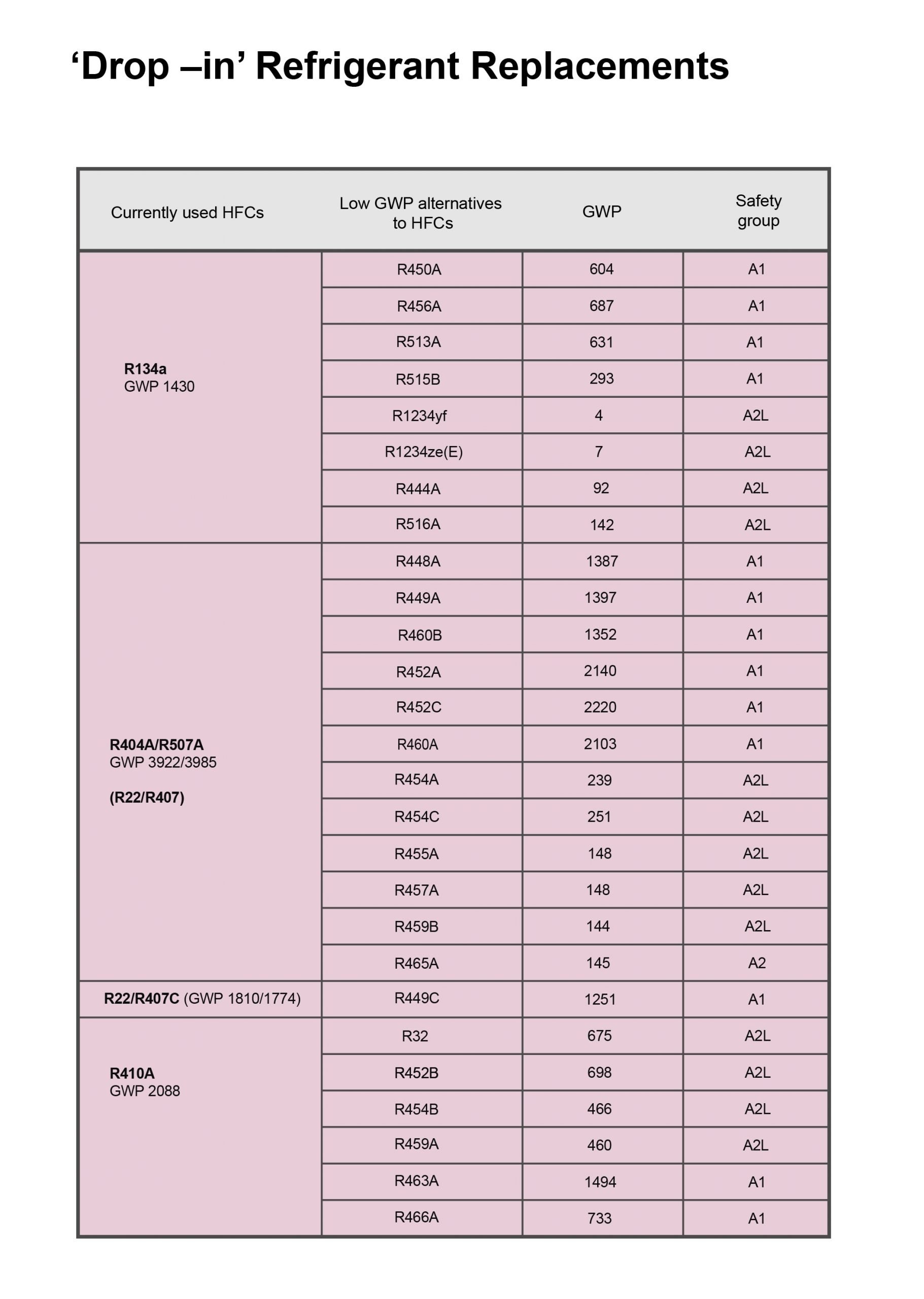

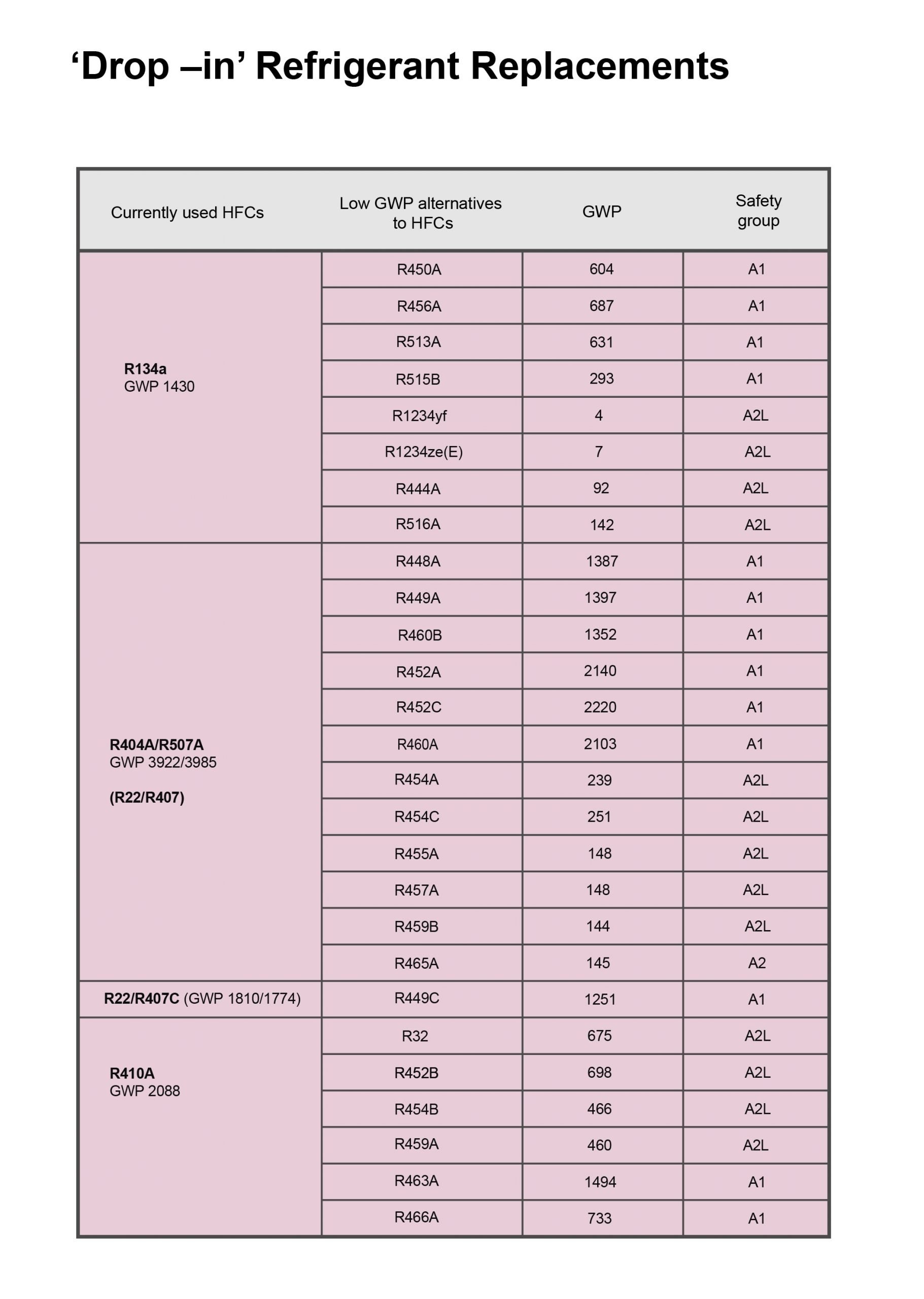

When assessing what to do with an existing F-gas refrigeration plant, it is often a requirement to retain the equipment and consider what options are available to allow for continued operation up to 2030 and beyond. One option is conversion of the refrigerant gas to a lower GWP alternative, examples of which can be found in figure B.

Fig.B ‘Drop-in’ Refrigerant Replacements