In March 2023, the European Parliament voted for a more aggressive phase-down of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) gases, aiming for a full phase-out by 2050 and banning HFCs and HFOs in multiple applications from January 2026 and 2027. However, negotiations aren’t expected to include until summer and on 5th April 2023, the European Council brought a more lenient approach, relaxing the quota step-down.

Please view our new updated article to find out more https://www.star-ref.co.uk/smart-thinking/the-new-fluorinated-gas-f-gas-regulation-phase-down-draft-proposal-april-2022/

New European Union (EU) regulations will dramatically affect the cost and availability of synthetic refrigerants with high global warming potential. As Europe begins its scheduled phase down of selected HFC gases, there is a need for food manufacturers, temperature controlled storage and distribution firms and other process industries to take a long term, strategic view of their refrigeration systems in order to mitigate significant future financial costs.

As the phase down of HFC gases with high global warming potential takes place over the next 15 years, there will be a rapid increase in cost and a marked decline in their availability.

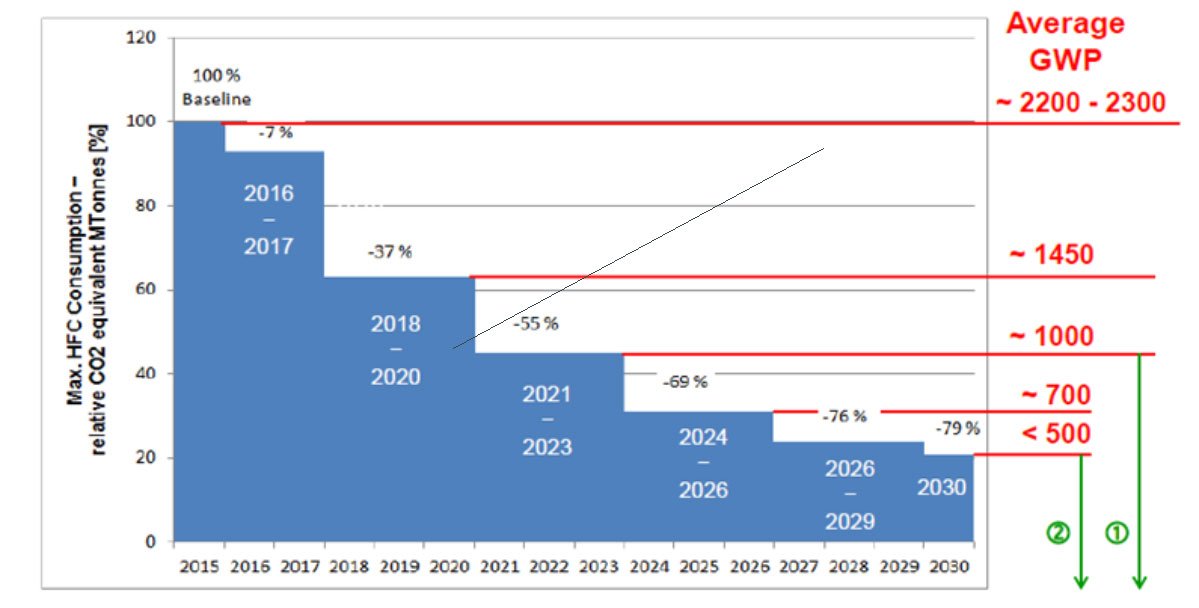

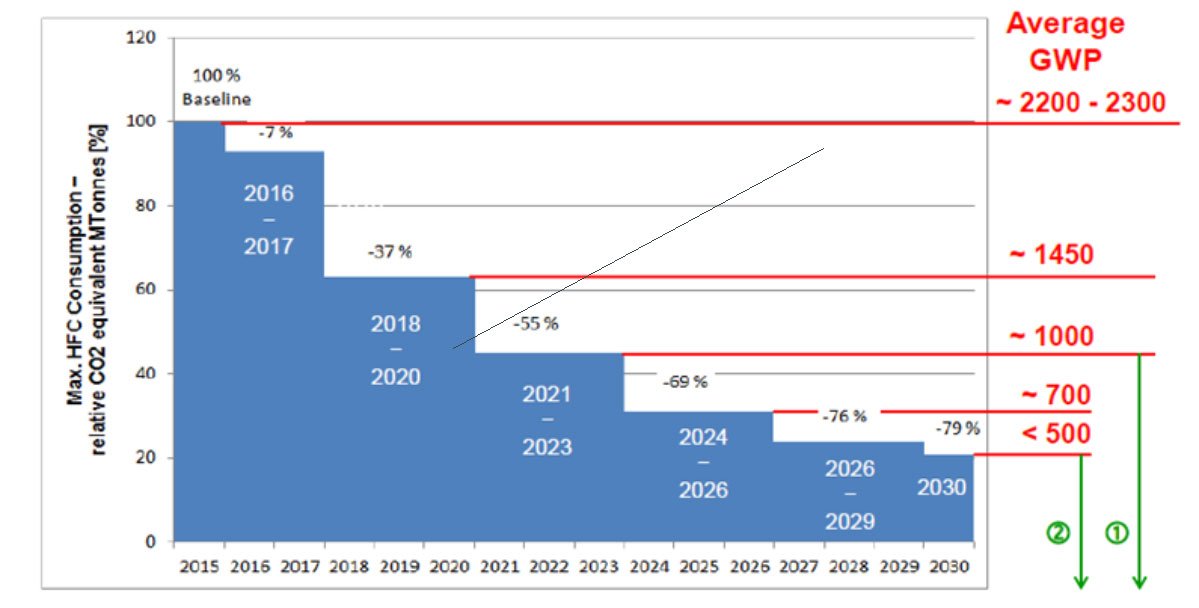

Refrigerant manufacturers have been allocated quotas for the HFC gases they can produce and supply within Europe. These quotas are measured in terms of carbon equivalent rather than kg, with the target to cut the current levels down to 63% by 2018, 45% by 2021 and 21% by 2030.

Over the past fifteen years, the refrigeration industry has seen the gradual phase out of synthetic, ozone-depleting refrigerants. From January 2015 the last of these HCFC gases, including R22, were banned in Europe.

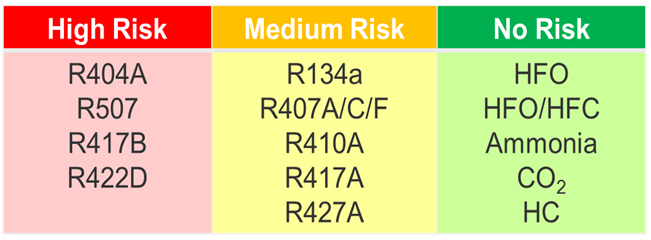

HFC refrigerants have been widely used as replacement gases for CFCs and HCFCs, but are now the focus of the EU’s F-Gas Regulations. Gases such as R404A and R507 have been found to have a high global warming effect and are currently the subject of a 15-year phase out programme.

The new F-Gas regulations set out the phase down timeframe for HFCs and impose greater requirements for leak testing.

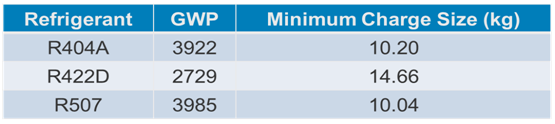

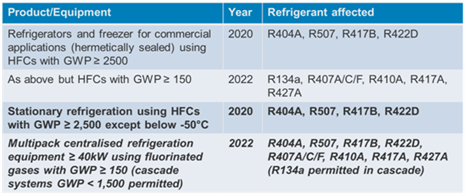

In addition to production phase downs, product and service bans will come into effect over the next seven years. These include a complete ban from 2020 on the use of virgin R404A and R507 gases for stationery refrigeration systems with a charge greater than 10kg.

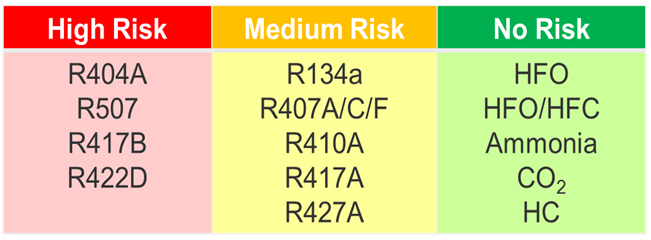

Do you know the level of risk of the gases you are using? High risk refrigerants over the next five years will become harder to source, and more expensive as they will be in high demand.

Users of refrigeration systems that operate on HFCs need to be aware that these gases are at risk in the near future. The message from Europe is clear: HFC refrigerants are not a viable long term solution and refrigeration plant operators should look to invest in futureproof cooling systems to avoid escalating costs and ensure uninterrupted business operation.

The new F-Gas regulation demands all companies keep comprehensive records of all gases and refrigerants used and details of any leakages. You must record:

- Quantity and type of gas installed

- Quantity of gas added*

- Whether gas is recycled/reclaimed

- Quantity of gas recovered

- Identity of who carried out the work

- Dates and results of leakage tests

- Measures taken to recover and dispose of refrigerant at end of life

- Copies kept for 5 years by operators and contractors

The expected phase-down timeframe for HFCs.

Installation, maintenance, service and leakage

The regulation also strengthens the requirement for the use of certified personnel. It is complsory for contractors to train staff working on refrigeration systems and carrying out one or more of the following tasks:

- Installation/service/maintenance

- Repair

- Decommissioning

- Leak checking

- Recovery

More information on F-Gas training and certification at i-Know.

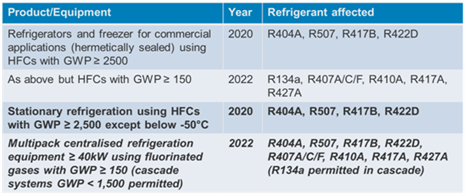

The phase down of certain refrigeration gases is accompanied by bans on non-sustainable equipment. The table below shows which products and refrigerants are affected:

There will also be a ban on the servicing of equipment with a charge of more than 40 tonnes CO2-eq from 2020: this affects refrigerants with a GWP ≥ 2,500. Between 2020 and 2030 it will be possible to use reclaimed or recycled refrigerant with a GWP ≥ 2,500.

Whilst refrigerant suppliers are busy developing new blended synthetic gases with lower global warming potential, there are long-established, natural alternatives, including CO2 and ammonia. Both refrigerants can achieve great efficiencies and are safe to use when managed by trained personnel. In addition, the use of advanced technologies such as low charge ammonia systems further reduces refrigerant related concerns, with charges reducing up to 90% (for an example of how this is achieved see the Brakes case study).

Don’t take risks!